A New Literate Playground

An essay

Language and letters give us the ability to express and interpret how we experience the world around us. But something is wrong. There seems to be a literal screen between us. We barely understand ourselves and each other anymore. We read and write less and less. Perhaps our alphabet is broken? It's time to look at literacy more broadly, with room for neurodiversity and synesthesia – a new literate playground where different senses work together. This is my quest for a conceptual framework that revises traditional views on learning, language, and literacy.

Fröbelen

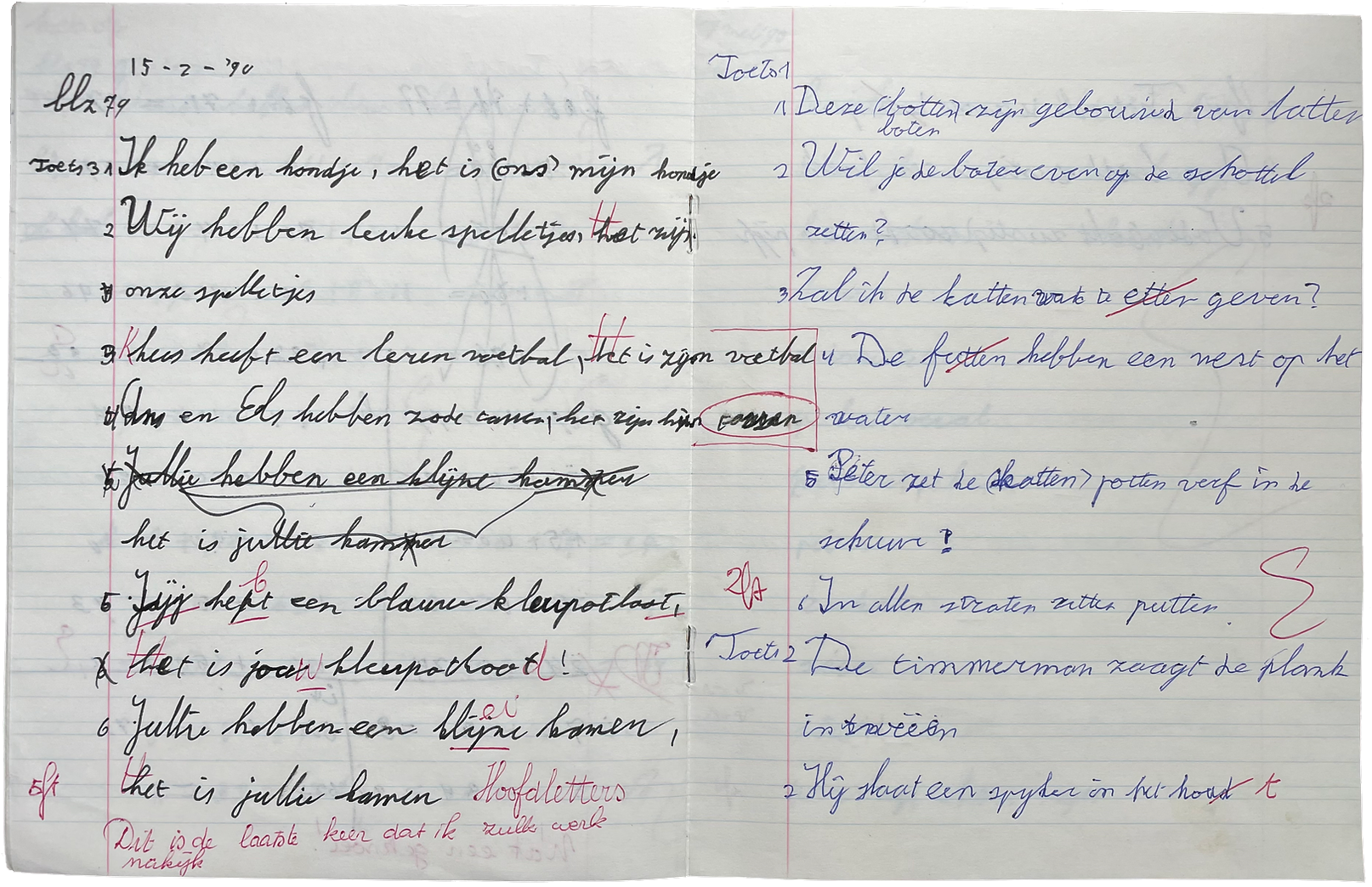

My whole life, I have had a healthy aversion to teachers. At least, that’s what I think. This likely stems from experiences in my early school years. I always struggled with reading and writing. Fine motor skills, formal rules, writing on the board—I found it dreadful. My school notebooks were filled with comments from ‘Mr. Daan’. In red ink, he wrote: "Capital letters! This is the last time I grade such work!", "What a mess," and "Even more messy!" These are not very motivating critiques to receive at age 9. School felt like an unsafe environment for me. Going to school was exhausting. All I wanted was to play outside. Slowly, I began to shut myself off from things. I didn't want to participate or be told that " Rob is more capable than he lets on." I've often wondered how it could be that I "couldn't learn well."

For me, the transition from playing with wooden blocks in the building corner to sitting still and learning to read, write, and do math in third grade was a difficult period. Growing up, my mother always encouraged me to "fröbel". I think the best translation is something like fiddle around. I thought it was just a saying and always viewed it as a pleasant but thoughtless pastime. During my research into my preschool years, I discovered that "Fröbelen" is actually a term used to describe the educational philosophy and methods of the German educator and crystallologist Friedrich Fröbel (1782 – 1852). Fröbel believed that education should focus on play and exploration. He invented the kindergarten and developed various "gifts," such as the block set. These materials were designed to provide children with a variety of sensory and intellectual experiences that would stimulate their curiosity, creativity, and critical thinking. Letters were not included in the "gifts" because Fröbel believed that formal education and instruction in reading and writing should only begin when the child was at least six years old. Something must have gone wrong for me around this time. I still make spelling mistakes, do not know how certain conjugations work and I feel dumb when I get "caught." Is my brain not working properly? Or is being literate something different from learning a language?

– My school notebooks were filled with comments from ‘Mr. Daan’. In red ink, he wrote: "Capital letters! This is the last time I grade such work!" These are not very motivating critiques to receive at age 9. School felt like an unsafe environment for me.

In the 1980s, Dutch schools developed a hyperfocus on correctly interpreting a text. There was often only one right (read: desired) answer. Just do what you’re told, don’t overthink. In that regard, the Dutch educate like they eat: functionally. This functional approach to literacy didn’t work for me. I learned outside the classroom—skateboarding, spray painting graffiti, or playing hockey. Because I liked many different things, I often fell a bit in between and was hard for many people to categorize—though they tried: while graffitiing, I was the "posh kid," at the hockey club the "shabby creative one." While at school I drowned in formal (language) rules, outside I had the space to discover how language actually works: that it is a dynamic phenomenon. At the hockey club, I discovered that the difference between a clubhouse and a canteen lies not in functionality but in the user’s culture. On the other hand, the mother of a teammate once asked me if I was sick when she overheard that I had put up some "throw-ups" on a wall over the weekend.

How Language Forms Our Reality

Graffiti gave me a greater spatial awareness of what is possible with letters and led me to attend art school. At the academy, I was broken down and rebuilt: forget everything you think you’ve learned so far. This is called Bildung and Gestalt, referring to the educational philosophy of Wolfgang Köhler (1887-1967). It’s a personal process of reinterpreting the world in which you discover who you are and what you do. According to Gestalt theory of learning, there is no fixed way to teach. It is a completely situational form of education, focused on what works for each individual student. What appeals to me is that it is a holistic, building, and active way of learning. You don’t learn in a linear manner (from A to B) but through a process called emergence: consequences build on consequences. This means everything is connected to everything else. This appearance can be experienced through the Gestalt theory of perception, which states that things are first perceived as a whole before all the parts are seen. You notice patterns and relationships that exist between objects and events. The method is primarily focused on how people process knowledge and not just on transmitting content or absorbing information.

During my time at the academy, I gained insight into my struggle with letters. I started designing my own fonts, making them from physical materials, and placing them in a spatial setting. I did this, just like fröbelen, unconsciously competent. It just felt good to cut letters out of sod, create meters-high numbers from Styrofoam, and weave strings between nails to form letters. I began to enjoy it. But at the same time, I wondered how it is possible that I struggled so much with letters? Some form of dyslexia seems to be evident. In The Gift of Dyslexia, Ronald D. Davis (1942) describes dyslexia as "a different way of thinking," with strong visual and spatial abilities. He developed a method where letters are formed with clay. This process makes abstract symbols more concrete, helping dyslexics better understand and remember letters. When I read this, I realized I had always done this. In that sense, I have turned my weakness into my strength. It opened a personal exploration into what we can learn from the perceptions of dyslexics and other, atypically wired brains.

Neurodivergency: Synthetic Synaesthesia as an Inclusive Communication Approach

To give literacy a broader function in daily life, we must strive for what I call a holistic and inclusive understanding. It’s difficult to describe your feeling or (sensory) experience to another person. In doing so, we tend to bypass words, as they can limit us. The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (1901 – 1981) argued that from birth, we are immersed in an existing language system that influences our sensory perception of reality, our self-image, and our desires. If we aim for a more encompassing literacy, we must open up to all our senses and relearn to communicate again. This requires us to create educational, communicative, and cultural environments where neurodiverse traits can flourish. A new approach to literacy might be found in synaesthesia. This is a neurological trait in the autism spectrum where senses blend. For example, people with synaesthesia might see colors when hearing sounds or taste flavors when reading words.

– To achieve a holistic understanding, dominant cultural narratives must be questioned and, in some cases, dismantled and rebuilt. This begins with our understanding of what a letter is.

The word synaesthesia means together (sun) and to experience (aesthesis). This shared experience not only stimulates multiple senses at once but also literally connects us. It is embedded in our language, as seen in expressions like "a warm color" or "a sharp taste." Unfortunately, we have become alienated from our senses. Before we could write, we were all synaesthetes. This can be traced back to the origins of our alphabet. The shapes of letters originated from meaningful icons with significant social implications. For instance, the letter A originated from the head of an ox, a very important asset those days. If we turn the A upside down, we still recognize the horns and head of the ox: . Where the arches meet in the letter B is a floor plan and the entrance to a house. And the letter C is a throwing stick used to hunt birds. The ongoing abstraction of Western letter forms has cut us off from our sensory connection with letters. Is it possible to make the social significance of letters relevant again? One possible solution could be to utilize synthetic synaesthesia: an artificial blending of the senses aimed at developing a more meaningful expression and understanding of language. This involves approaching language through scent, taste, touch, and other sensory possibilities, which compel us to discover and appreciate new ways of communicating.

A Pedagogical Approach to a New Literate Playground

To achieve a holistic understanding, dominant cultural narratives must be questioned and, in some cases, dismantled and rebuilt. This begins with our understanding of what a letter is. To do this, we have to go back to our childhood, before the first encounter with letters. The ideas of Fröbel provide starting points for this. However, we must also articulate the understanding of the social context of letters. Where do our letters come from, and what do they mean? This allows us to enter a new relationship with abstract symbols, and even a new emergence of language is possible through other senses than just sight and sound. I propose three starting points that can be expanded:

Cultural Memory: The Voyage of the Alphabet

The alphabet is more than a series of symbols; it is a product of human history and culture. Therefore, it is important to become acquainted with the historical origins of the alphabet. This approach aligns with the idea of "cultural memory" proposed by cultural philosopher Vilém Flusser (1920 – 1991), who believed that understanding the origins of human communication is crucial for giving meaning to our experiences. By exploring the roots of the alphabet, delving into the evolution of writing systems and associated writing tools, we can reestablish a connection with the alphabet. This narrative approach adds deeper meaning and context to design and communication solutions, transforming the alphabet from an abstract series of shapes back into a cultural artifact with rich stories.

Perceptive Knowledge: A Multi-Sensory Approach to Letters

From our knowledge of the historical significance of letters, we can create reinterpretations. By taking full sensory perception as our starting point, we allow for a wider range of possibilities and thus more inclusive communication. The sense of smell, for example, is a highly suggestive aspect of human experience. Scents can evoke memories, emotions, and connections. By introducing the scent of an ox, a house, a throwing stick, etc., into our playground, we add a new, playful dimension to literacy. Each letter can be associated with a unique social context that is captured in a sensory state, such as taste, smell, touch. This approach bridges the gap between the abstract and the concrete, transforming the alphabet into a sensory adventure.

Modular Letter Shapes: The Cognitive Palette

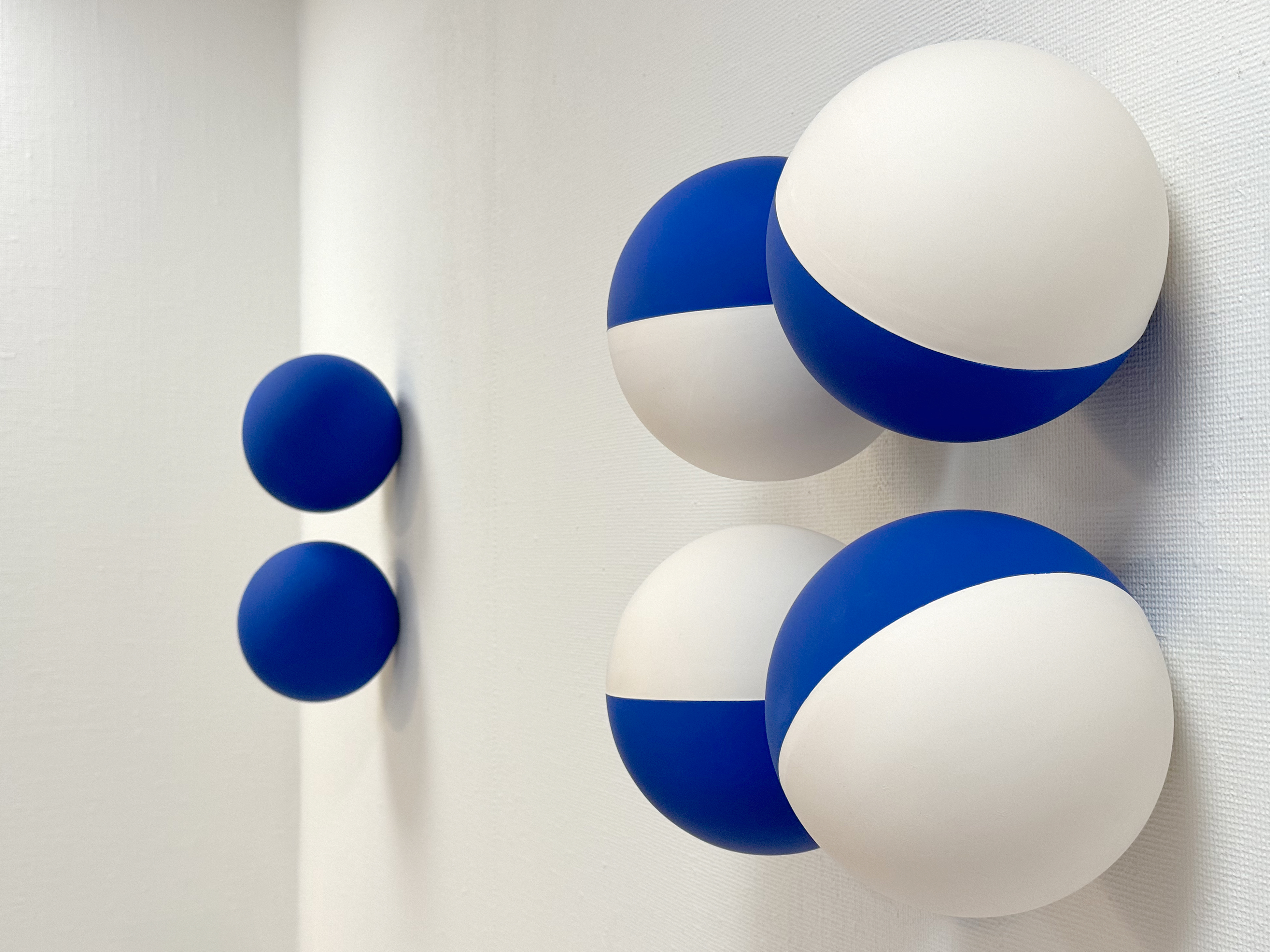

By incorporating modular letter shapes into Fröbel’s methodology, emergence is brought to the forefront of literacy education: when does a whole of composition, material, and experience transform into a letter and become a carrier of information? First, we see the whole before we interpret its parts. Just as art evokes a sense of wonder and expression, we can use sensory modular (letter)forms in a playful way to become literate.

In conclusion: if we want to introduce this playground for inclusive literacy, we must start to radically reinterpret the smallest building blocks of our language. A crucial role in this lies with artists, writers and designers. Let’s move beyond the screen and restore a socially and tangibly meaningful understanding of what letters are. By embracing sensory letter forms, we harness the aesthetic appeal and cognitive benefits of letter design while playfully promoting literacy. As the 21st century unfolds, it is essential to reconsider and renew our approach to learning, language, and literacy at both young and advanced ages. The artistic alchemy of sensory letter forms, synthetic synaesthesia, and a historical perspective on the alphabet opens doors to a richer, more engaging, and ultimately more inclusive path to literacy. By combining discovery through play from the pedagogy of Frederik Fröbel, perceiving the whole before seeing the parts from the Bildung and Gestalt theory of Wolfgang Köhler and developing synthetic synesthesia, we literally expand our communicative world. This creates a new literate playground for a sensory, inclusive, and deeply meaningful language journey that I would have loved to experience as a child.